Television fans are not complicated creatures. It is no mystery that if people are entertained by something, they tend to engage with it. In the age of the Convergence Era, this phenomenon proves to be true more than ever. After all, entertainment is now as simple as a click of a button—a button that can be anywhere at any time. Suzanna Scott reiterates this point in her article, “Battlestar Galactica: Fans and Ancillary Content,” by exploring the growing relationship between television fans and what she describes as “ancillary content.” According to Scott, ancillary content can be found on a television series’ website in the form of webisodes, webcomics, episodic podcasts, blogs/vlogs, alternate reality games (ARGs), and more (321). For the sake of Scott’s argument, she focuses on a series of episodic podcasts that were recorded by Ronald D. Moore, creator and executive producer of Battlestar Galactica, while it was still on the air. These weekly podcasts helped fill in the missing information between episodes that would otherwise leave viewers to “debate potential answers and scribble in the textual gaps and margins to create and circulate answers of their own.” (321) Not to mention, the podcasts also served as Moore’s way of providing context and justification for narrative decisions.

While these functions may sound beneficial to the Battlestar Galactica fan-base, Scott claims otherwise in her article. Rather than innocently providing entertainment to fans, Scott views the increase of producer and creator podcasts as the television industry’s attempt to “maintain interpretive power.” (321) In other words, she is arguing that ancillary content does not allow for audiences to develop their own fan texts before a show’s creators fill in the narrative gaps and ambiguities for them. This could be viewed as what Scott refers to as “ideological control,” because the producers and creators decide what the “intended” and “preferred” interpretations of the text should be. As a result, Scott claims that this shrinks the amount of creative opportunity available for fans, even if the content is inspirational.

In addition to decreasing creative opportunity, Scott also argues that ancillary content facilitates more of a monologic than dialogic relationship with fans. In other words, while audiences may be able to talk back to their television screen online, the conversation is not a back-and-forth dialogue.

I do not doubt the validity of Scott’s arguments when it comes to the ancillary content associated with Battlestar Galactica. However, it is worth exploring whether or not her claims apply when it comes to a different television series. Considering the vast amount of ancillary content associated with the television show This Is Us, it makes for a worth-while comparison in terms of producer and fan-base relations.

Unlike the science fiction media franchise that is Battlestar Galactica, NBC’s This Is Us is a comedy-drama television series. On September 20, 2016, the day of its premiere, the world was introduced to the Pearson family: Jack, Rebecca, Randall, Kate, and Kevin. Throughout its now three seasons of being on the air, the audience has been through a great deal of experiences with the previously mentioned characters of the show. For starters, the adoption of Randall after his birthfather left him at a fire station, the development of Jack and Rebecca’s relationship, and the realistic hardships that seem inevitable for this Philadelphia family. Unlike most shows, This Is Us does not tell its story in chronological order. Instead, the story is told with the help of multiple flashbacks that depict the Pearson’s past and present experiences. This always makes for entertaining episodes that play out the life of a family that may be unique but, nonetheless, manages to be relatable to each of its 10.3 million viewers (Jefferson n.pag.).

Of the 10.3 million viewers that tune in to watch This Is Us every week, 105k of them are subscribed to the “This Is Us: Aftershow” on YouTube. Much like Battlestar Galactica’s producer-made podcast, the Aftershow is hosted by Executive Producer, Isaac Aptaker, and Co-Producer, Kay Oyegun. However, being hosted by producers is not the only similarity between the two podcast-like creations. Both offer commentary, context, and predictions from the producers episodically. An example of this dialogue can be viewed in the video below, titled “Aftershow: Season 3 Episode 18 – This Is Us.”

Just below the video, notable fan-comments can be found:

All of the comments above have one thing in common: fans are trying to fill in the gaps of the storyline and they are making predictions for future episodes. However, according to Scott’s study of Battlestar Galactica’s ancillary content, the ability for fans to make these kinds of comments is difficult because a show’s creators fill in the narrative gaps and ambiguities for them. While this might apply to fans of Battlestar Galactica, it appears that the This Is Us producers leave room for mystery, even when utilizing ancillary content. Ultimately, this seems to leave the fans feeling satisfied, especially when looking at some of the other comments left below the video:

In addition to subscribing to the Aftershow, fans have the liberty to follow This Is Us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. From the looks of it, many fans act on this opportunity, with 3.9 million followers on Facebook, 412k followers on Twitter, and 1.3 million followers on Instagram.

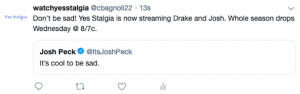

Needless to say, this further suggests that This Is Us has an incredibly strong fan-base across all platforms. While this could and should be viewed as the television industry’s way of furthering their agenda to keep creative power in their own hands, I still think it allows for more of a dialogic relationship than Scott could have predicted. This could easily be attributed to the fact that social media was not as developed at the time of her analysis. Now, social media gives fans the opportunity to interact with and respond to producers of their favorite shows, even if a back-and-forth conversation is only an illusion to make fans feel as if their voices are being heard. Take this interaction on Twitter, for example:

I would also argue that even if there is a strong power-dynamic between the television industry and fans, not all creative opportunity for fans is lost. This is especially evident when viewing the vast amount of fan-made content on the Internet.

For example, there are six podcasts created by fans alone, one of which is shown below, titled “This Is Us Podcast with Kei & Clyde.”

Furthering this point, the website “Vulture” has an entire webpage dedicated to a This Is Us blog.

Among other fan-made content consists of social media pages, like the ones pictured below.

After reading about Scott’s analysis, viewing This Is Us ancillary content, and analyzing This Is Us fan-made content, I have come to a final conclusion. My conclusion is as follows: Scott was correct to claim that producers create ancillary content as means of maintaining power in the television industry. However, it does not hold true that this always takes away interpretive power and creativity for all fan-bases. This is demonstrated perfectly in my analysis of ancillary content associated with This Is Us. While producers are creating ancillary content for fans, its point is not to interpret the show for them. Instead, it appears that the This Is Us producers participate in its creation to keep fans connected and engaged in their community. Therefore, the This Is Us fan-base is tightly bonded not only because of their love for the show, but because of their trust in the producers to value them as fans. While the end goal here is still money and power, it is accomplished in two different ways (i.e. filling in gaps for fans vs. leaving room for questions). Not to mention, the Internet still allows for a great amount of creativity from fans that wish to express their thoughts about shows in the form of social media posts, art, writing, or otherwise.

While it might not be a surprise that the power of the television industry is alive and well today, it is worth noting that ancillary content does not necessarily have to affect the interpretive and creative power of fans, especially when it comes to This Is Us.